Today’s Gospel reading is a bit of a minefield – you have to be careful where you put your feet. It’s very easy to end up saying something as self congratulatory as ‘Heavenly Father, I thank you that I’m not like that Pharisee, thinking I’m better than everyone else’ thereby becoming exactly like the Pharisee.

Then there’s the trap of competing against each other in humility. There’s a good story about 3 Rabbis who came to their synagogue to pray. The first Rabbi threw himself on the floor proclaiming ‘Have mercy on me God because I’m unworthy even to confess my sins’. The second Rabbi entered and did the same. The third came in, threw himself on the floor and said the same, ‘Have mercy on me God for I’m unworthy even to confess my sins’. At which point the first Rabbi got up and said indignantly ‘How dare you two pretend you’re more unworthy than I am!’

And then there’s the concern that groups of people who have historically been considered sinful, wicked or evil might not need to be reminded that they are unrighteous. We might think of women, who have traditionally been seen as tempters, unclean and unworthy. There are gay people whose quest for love could lead them to prison as recently as 1967 in the UK, and can still result in imprisonment or death in many places across the world. So, yes, there are some who need to be told ‘You’re OK, you’re a child of God, made in God’s image – and God loves you!’

And there are people who are really good people, who devote their lives to good causes, to work for justice and peace. People whom we hold in high esteem – think of Desmond Tutu, Mother Teresa, the Dali Lama, Martin Luther King. And maybe Greta Thumberg. Where do they fit in to this story.

And then there’s us. Where is our place in Jesus’ parable? We’re not perfect but we’re decent, upright people, who do our best, are faithful church attenders, and have probably never had a brush with the law. We would be mortified if we were caught up in a situation where we were found guilty of wrongdoing or even accused unjustly. It is a terrible thing to be a decent, hard working person wrongly accused of something which throws you into disrepute – it’s humiliating and very frightening suddenly to find yourself in the same camp as wrongdoers. Our identity is one of decency.

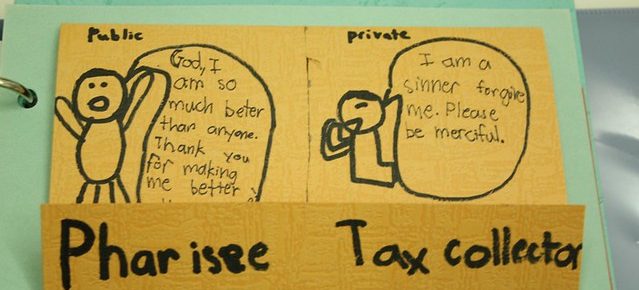

I think two very important things lie at the root of this parable, and neither of them are to do with us as human beings, but about God.

The first is God’s infinite goodness and righteousness. I think this is something we easily forget. God is good beyond our knowing and understanding. God is greater than our minds can comprehend. God’s grandeur spans all time, all space – we can never find its beginning or its end. It’s easy to forget this. It’s easy for us to domesticate God, to make God in our own image – rather small, domestic and finite. Gone are majesty, awe, wonder. When this happens it is easy to forget, as did the Pharisee in the parable, that no matter how good we are, we can’t come anywhere near the goodness and perfection of God. This is true for everyone – even the wronged, even those stigmatised by society, even those who have carried their burdens of shame all their lives.

I guess it’s difficult for us to remember a goodness that is beyond our comprehension. But we have to try. And when we do, suddenly we find we’re not the centre of the universe, we realise ‘it’s not all about me’. And that place is the beginning of humility. It’s rather like looking at the majesty of the night sky and suddenly realising how small you are.

The second thing we need to remember is that this infinitely good, everlastingly righteous God loves us, each one of us. This is a love without any ‘ifs’. God doesn’t say, ‘if you’re good I’ll love you’. God doesn’t even love us ‘despite who we are’. God loves us because of who we are. And this includes those whom human society casts aside, those who are frowned upon, stigmatised, derided.

This is hard for us to swallow. There are some who we count as beyond the pale – outside the fence. Those whose behaviour has caused terrible pain to others, those who show no remorse. Those who are infinitely less righteous than we are – and there we are, back with the Pharisee again.

I think God must see through us – beyond our righteousness and beyond our wrongdoing too, beyond the wounds that make us behave as we do. Had the tax collector in today’s Gospel continued to turn up week by week, calling out to God, but never turning his life around, God would still love him.

I truly believe that, in the end, God never turns us away. In God’s eyes we are all sinners, and in God’s eyes we are all loved. But I do think it is possible for us to turn God away – either because we find evil preferable to good, or maybe because God just isn’t good enough.

I was just coming to the end of writing this sermon when one of my dogs attempted to jump onto the worktop and broke a pile of plates waiting to be put away. You naughty dog! You bad dog, I said!