Easter 1 (2nd of Easter)

The story of doubting Thomas is very familiar. I think many people admire him because he dared to be honest about his doubts – he didn’t just go along with what everyone else was saying – he had to get there in his way. A person of integrity – someone who needed to see and understand for himself. Really, he should be known as ‘Questioning Thomas’, not Doubting Thomas. He was a man of great faith: he took Christianity all the way to India, where the church he founded still thrives today – this really isn’t the work of a doubter.

Questioning Thomas: Questioning is what keeps our faith alive. It enables us to dig deeper, to reach new and deeper understandings, to have a richer faith. Ultimately, questioning leads to action – as was the case with Thomas. It also leads to contemplation – that point when we come to realise that God is a mystery before whom we can stand only in silent reverence – the place where words cease.

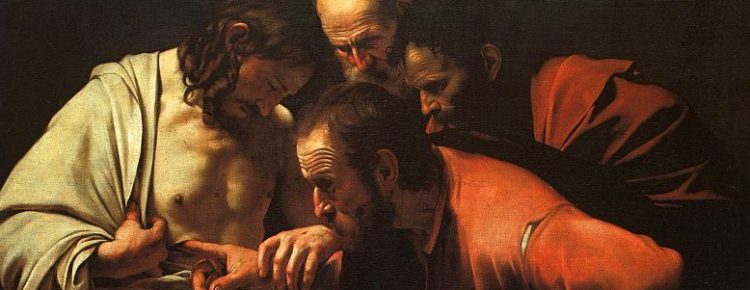

Many of the images of the events of today’s Gospel reading are rather gruesome – fingers in deep wounds – like something from a rather brutal TV crime drama. However gruesome, I think bringing these wounds to our attention is Thomas’ gift to us. Were it not for him we would have forgotten that Jesus still bears the scars of his crucifixion after his resurrection from death. Jesus had already shown his wounds to the other disciples – but somehow this doesn’t stick in our minds. It’s Thomas who makes us remember the wounds. St John brings these wounds into this account twice though – he is telling us something important.

Now wouldn’t you think that God would have healed those wounds on Jesus’ hands, feet and side when Jesus was raised from death? It seems very odd, at first, that they’re still there. We imagine that, when our time comes and we step from death into new life, our wounds – visible and invisible – will have disappeared. We will be perfect. And yet here is Jesus, still with his wounds and scars. How can this be.

A few weeks ago, I attended a workshop entitled ‘Vision 2026 – does it have a theology?’ We were told it doesn’t which really isn’t really encouraging and it did rather make me wonder what we are all doing there. But then we were asked to reflect on the Vision 2026 strapline ‘Healthy Churches Transforming Communities’. What is a healthy church, we were asked. My response was ‘one that is full of broken people’ and I got the feeling that there weren’t many people present who agreed with me. We have a tendency to equate faith with perfection. This is a very dangerous idea which has raised it’s ugly head in many times and places. In the recent past it was a theology which underpinned South African Apartheid – those who enjoyed privilege, wealth and health were those whom God had blessed for their faith. The poor and the sick didn’t deserve God’s love – their poverty and illness are a sign of this. This theology is also very common in the USA and it seems it is getting a toe hold here in some evangelical churches.

As someone who has scars on every limb, and is about to acquire a few more, I think the link between faith and health – perfection – is questionable. After all, Jesus had scars and carried them with him even in the resurrection. Jesus was a broken person. We all have scars in one way or another – emotional or psychological scars as well as physical ones. Abuse in childhood or in an adult relationship, disabilities of mind or body, illnesses, injuries and accidents – these are our scars. I am personally aware of the damage that sustained bullying can do, and of how easy it is for institutions to support the perpetrator rather than the victim. Nevertheless, our wounds are our humanity. And these are something we share with God – now there’s an interesting idea – a God with wounds and scars.

To me there is something very dangerous in the idea of churches full of ‘healthy’ people. The effect is easy to see – these churches see themselves as successful, examples of how it should be done, and extra resources are duly heaped upon them.

This is not how Jesus intended it to be. He didn’t seek out the healthy and successful. He was always with the outcasts, sinners and those who’d made a complete mess of their lives. OK he healed the sick and enabled the wealthy to divest themselves of it all. But all these people still carried their wounds and scars. This is what made them who they were. And Jesus came to count himself amongst them in his crucifixion and resurrection.

Practically speaking, this means we have admit our own brokenness and we have to allow others to be broken too. Sometimes our own behaviour and that of others is hard to cope with, precisely because it’s all a bit out of kilter and wonky. Clergy are no exception – we’re broken too, and it is often more difficult for us to share that brokenness with others.

In truth, our wounds and wonkiness are part of who we are. It is as if Jesus comes to us and wishes to place his finger in our wounds if we will let him – only then we will know that we are known and loved by God. And we will be healed. But we will still have our scars – they remind us that we are loved truly for who we are, not who we would like to be, or who we feel we ought to be, or who we are on a good day, or who others would like us to be.

The wounded healer is one of us and his wounds are part of who he is, just as our wounds are part of who we are. We need to learn to love them precisely because God knows and loves them. We are a church full of broken people. We need to remember that in our dealings with one another. No pedestals, no superiority, but gracious and loving understanding.