Easter 3. 2017

I think if I were asked to choose one passage from the Bible as my absolute favourite it might well be today’s Gospel passage – the story of the Road to Emmaus

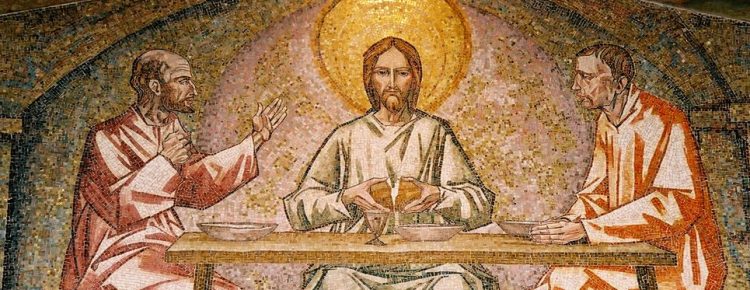

That moment when perhaps time stood still: after the journey and the encounter on the road, when the disciples sat down at the table and then the stranger broke the bread and suddenly they knew that this was Jesus, their teacher and friend – just as he vanishes into thin air. Such a simple action – breaking bread – it was all that was needed.

It is a priestly privilege to do this same thing today – to break bread. It is also a priestly responsibility not to get in the way – to enable people to focus on this simple but important act of breaking bread – so that today’s followers may also recognise their teacher and their friend, Jesus Christ.

It is important to watch this act – the breaking of the bread – a good moment for you to look up from your service books and see, understand, that in this action, Jesus is with us: to understand that incomprehensible truth that he is risen. These small things are so important for our faith – to remember to lift our heads and witness the breaking of bread and to count ourselves as fellow travellers and witnesses with those disciples on the Emmaus Road all those years ago. We’re part of the ongoing story that reaches beyond the pages of the Bible into our own time and our own place. In the breaking of the bread, Jesus is with us – the risen one, our familiar teacher and friend. Our Saviour.

Our familiar friend – this is true. But in this wonderful story we see another truth: another example of the uncatchability of Jesus. He said to Mary Magdalene, the first witness to the resurrection ‘do not hold on to me’, and we can see the same here. Once the two travellers have recognised Jesus, he is gone. They can’t catch hold of him, they can’t keep him, they can’t put him in a box – he is gone. The same is true of the empty tomb: at the heart of our faith is absence – ‘he is not here, he is risen’.

The same is true for us in two senses:

First, our God often seems absent. Sometimes it is as if we too are looking at an empty tomb: or that we arrive just after Jesus has left – he always seems tantalisingly just ahead of us, just moved on – and we can spend a lifetime looking, searching – like Baboushka.

This is to be expected, and we can take consolation from Mary, from the travellers on the Emmaus Road, from the eleven gathered in the upper room. Jesus was there – then he wasn’t, always just beyond our understanding, always too quick for us to grasp. At these times, to watch the breaking of the bread is even more important but in this action, Jesus has promised always to be present. Once we recognise him here we are more able to recognise him in other simple and lowly things: as William Blake wrote

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

Secondly, Jesus – God – is always beyond our grasp. God is not comprehensible, catchable, tameable. Much as I love the modern language we now use in our liturgy, there is a tendency to be ‘over familiar’ with God, now we have lost the Thees and Thous. With our focus on God’s immanence (God here with us) upon which we focus for much of the year, it is also important that we remember God’s transcendence – God is beyond our knowing, bigger than our imagining. We cannot truly hold God’s entirety in our hearts: we see and understand only in part. We need to beware of building a God in our own image – small enough for us to tame, tame enough to be safe, safe enough not to be God at all.

The Emmaus story teaches us one more essential thing, something which is connected to allowing God to be bigger than our human constructs. The man who turned out to be Jesus was a stranger – someone unfamiliar, unknown. And so must we be prepared to meet our Risen Saviour in those who are strange to us, someone other than us. It is of great importance that we remember this – before we close our borders, leave

the refugees to suffer without our help, turn our backs on starving people in Africa, we have to remember that, in their faces, we may have seen Jesus, had we bothered to look. I would ask you to dwell on this as you consider who you will use your vote in the forthcoming elections.

This is never easy. We are always more comfortable with people who are like we are. But it is essential for us, nonetheless, for us to open our eyes and our hearts, and to look for Jesus Christ in the faces of strangers.

I finish we a lovely story of Jewish teaching;

The rabbi asks his students: ‘How can we determine the hour of dawn, when the night ends and the day begins?’

One of his students suggested: ‘When from a distance you can distinguish between a dog and a sheep.’

‘No,’ was the answer of the rabbi.

‘Is it when one can distinguish between a fig tree and a

grapevine?’ asked a second student.

‘No,’ said the rabbi.

‘Please tell us the answer then,’ said the students.

‘It is, then,’ said the wise teacher, ‘when you can look into the face of human beings and you have enough light to recognise them as your brothers and sisters. Up until then it is night, and darkness is still with us.’ Amen